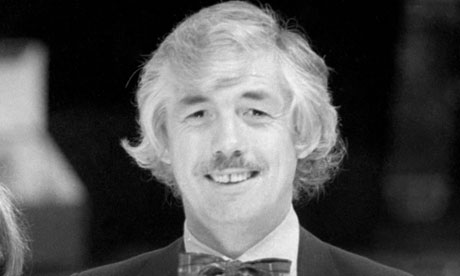

George Kimball was as well known for his disdain of authority as he was for his ability to meet deadlines

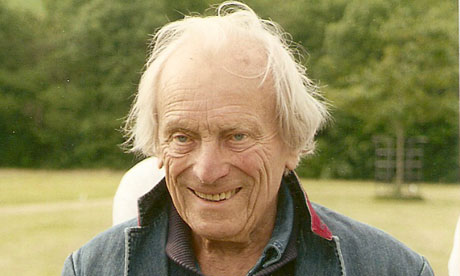

George Kimball, who has died aged 67, deserves a place with the great sportswriters. As a columnist for the Boston Phoenix and Boston Herald, he covered all sports, displaying an uncanny ability to cut through the persiflage and get to the core of a story or a personality.

He was a rare raconteur who could write with the same fluency with which he spun stories, conveying through the grace of his prose the intimacy of an audience gathered in a smoky bar. A robust figure, with ginger beard and pot belly, chain-smoking Lucky Strikes, Kimball was as well known for his disdain of authority as he was for his ability to meet deadlines, no matter how hard the previous night's session had been.

When he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer of the oesophagus in 2005, he was given six months to live. He ignored the doctors, continued smoking, and began working to leave behind something less ephemeral than his thousands of columns. One result was Four Kings (2008), a tale of the great middleweights Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran, who dominated boxing in the 1980s, its last era of greatness. Any fight that drew George to Britain, or even better Ireland, became a holiday in itself. The British boxing press recognised one of their own, and to be caught at a bar between George and Hugh McIlvanney, Colin Hart or Ian Wooldridge was, infinitely preferable to negotiations with promoters or indeed my bosses in New York.

Although George fits in seamlessly with the Runyonesque traditions of great boxing writers, his route to the daily papers was unusual. He came to this hardboiled field as a literary hippie. Born in Grass Valley, California, he was the son of an army colonel, grew up on bases around the world and entered the University of Kansas, in the city of Lawrence, on a US navy officer training scholarship.

He was soon drawn to campus protest against the Vietnam war. In 1965 he was expelled for picketing the local draft board, having been arrested for lewd conduct over an offensive placard. It was the first of half a dozen arrests. According to Kimball, his father claimed he would have retired as a general had his son's anti-war profile not been so high.

Having worked on a poetry magazine, Grist, he headed for New York's East Village poetry scene, and got a job at the Scott Meredith literary agency, assessing the work of would-be writers and ghostwriting. His poetry was published in the Paris Review, and in 1967 the Olympia Press brought out his sole novel, Only Skin Deep.

He sold pieces to the Village Voice, Rolling Stone and Playboy, but in 1970 returned to Kansas to run for sheriff against the Republican incumbent who had arrested him in 1965. He ran unopposed in the Democratic primary as the self-proclaimed leader of the "Lawrence Liberation Front" (a hippy group), and used the unwinnable election to indulge in political theatre which included an appearance by the radical activist Abbie Hoffman.

After the election, he moved to Boston and its excellent weekly "alternative" paper, the Phoenix. His column, the Sporting Eye, was an immediate hit, drawing the counterculture community into the world of sport. Its title referred to his own glass eye, which he claimed replaced one lost in a youthful bar-room brawl.

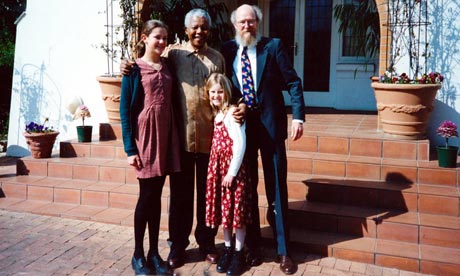

Kimball finally quit the Phoenix in 1979 after one too many confrontations with his editors. He moved to the Boston Herald in 1980, where his columns ran until his retirement in 2005. In 1997 he began a column, America at Large, for the Irish Times. His contributions were collected in a book of the same name, published in 2008. He also co-wrote Chairman of the Boards: Master of the Mile (2008), the runner Eamonn Coghlan's autobiography. After Four Kings, Kimball edited two collections of boxing writing with John Schulian and published a collection of his own boxing writing, Manly Art, earlier this year.

Kimball is survived by his fourth wife, Marge, whom he married in 2004 in a ceremony conducted by George Foreman, and by a son and daughter.

• George Edward Kimball, sportswriter, born 20 December 1943; died 6 July 2011

He was a rare raconteur who could write with the same fluency with which he spun stories, conveying through the grace of his prose the intimacy of an audience gathered in a smoky bar. A robust figure, with ginger beard and pot belly, chain-smoking Lucky Strikes, Kimball was as well known for his disdain of authority as he was for his ability to meet deadlines, no matter how hard the previous night's session had been.

When he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer of the oesophagus in 2005, he was given six months to live. He ignored the doctors, continued smoking, and began working to leave behind something less ephemeral than his thousands of columns. One result was Four Kings (2008), a tale of the great middleweights Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran, who dominated boxing in the 1980s, its last era of greatness. Any fight that drew George to Britain, or even better Ireland, became a holiday in itself. The British boxing press recognised one of their own, and to be caught at a bar between George and Hugh McIlvanney, Colin Hart or Ian Wooldridge was, infinitely preferable to negotiations with promoters or indeed my bosses in New York.

Although George fits in seamlessly with the Runyonesque traditions of great boxing writers, his route to the daily papers was unusual. He came to this hardboiled field as a literary hippie. Born in Grass Valley, California, he was the son of an army colonel, grew up on bases around the world and entered the University of Kansas, in the city of Lawrence, on a US navy officer training scholarship.

He was soon drawn to campus protest against the Vietnam war. In 1965 he was expelled for picketing the local draft board, having been arrested for lewd conduct over an offensive placard. It was the first of half a dozen arrests. According to Kimball, his father claimed he would have retired as a general had his son's anti-war profile not been so high.

Having worked on a poetry magazine, Grist, he headed for New York's East Village poetry scene, and got a job at the Scott Meredith literary agency, assessing the work of would-be writers and ghostwriting. His poetry was published in the Paris Review, and in 1967 the Olympia Press brought out his sole novel, Only Skin Deep.

He sold pieces to the Village Voice, Rolling Stone and Playboy, but in 1970 returned to Kansas to run for sheriff against the Republican incumbent who had arrested him in 1965. He ran unopposed in the Democratic primary as the self-proclaimed leader of the "Lawrence Liberation Front" (a hippy group), and used the unwinnable election to indulge in political theatre which included an appearance by the radical activist Abbie Hoffman.

After the election, he moved to Boston and its excellent weekly "alternative" paper, the Phoenix. His column, the Sporting Eye, was an immediate hit, drawing the counterculture community into the world of sport. Its title referred to his own glass eye, which he claimed replaced one lost in a youthful bar-room brawl.

Kimball finally quit the Phoenix in 1979 after one too many confrontations with his editors. He moved to the Boston Herald in 1980, where his columns ran until his retirement in 2005. In 1997 he began a column, America at Large, for the Irish Times. His contributions were collected in a book of the same name, published in 2008. He also co-wrote Chairman of the Boards: Master of the Mile (2008), the runner Eamonn Coghlan's autobiography. After Four Kings, Kimball edited two collections of boxing writing with John Schulian and published a collection of his own boxing writing, Manly Art, earlier this year.

Kimball is survived by his fourth wife, Marge, whom he married in 2004 in a ceremony conducted by George Foreman, and by a son and daughter.

• George Edward Kimball, sportswriter, born 20 December 1943; died 6 July 2011