Martin Woodhouse designed a Logical Truth Computer nicknamed Lettuce.

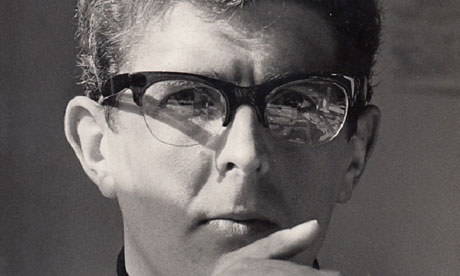

Martin Woodhouse, who has died aged 78, had what he called "a grasshopper mind" which led him to leap from one interest to another. Trained as a doctor, he qualified but was not registered and never practised; instead, he began exploring the concept of artificial intelligence and created a logic machine at Cambridge. Another change in direction followed his service with the RAF, when he became a television screenwriter, penning episodes of the puppet show Supercar and The Avengers, among others.

After writing a number of tongue-in-cheek thrillers shot through with action, cynicism and humour, Woodhouse combined many of his interests (electronics, computers, writing) in creating the first e-books. His programme, Illumination, developed in 1987-88, was capable of "publishing" full-length novels, with both text and graphics, on a 3.5in floppy disc. Between 1992 and 1995, Illumination Publishing produced some 20 e-books, from volumes of poetry and children's short stories, to illustrated brochures and a 190-page colour graphic novel. In recent years he had been developing the Lightbook, an e-reader powered by sunlight that could be mass produced for as little as $10 per unit and used for education in developing nations.

Woodhouse was born in Romford, Essex, the son of a local doctor, Robert Woodhouse, and his wife, Josephine, who wrote verse as Anthony Woodhouse and won the Newdigate prize for English verse while she was at Oxford. Martin was educated at the cathedral choir school, Salisbury, and Oundle school, Northamptonshire, well away from the blitz in London. His older half-brother, Robert, a Mosquito pilot with the RAF's 107 Squadron, was killed over Arnhem in 1944.

Woodhouse studied for a BA in natural sciences at Downing College, Cambridge, before attending medical school at St Mary's hospital, Paddington. He studied experimental psychology under Richard Gregory and did postgraduate research at the Medical Research Council Applied Psychology Unit, where he designed and built the Logical Truth Computer (LTC, nicknamed Lettuce) to investigate and compare the differences between human and machine intelligence.

His research was interrupted when he was called up for national service with the RAF in 1958, serving as a pilot officer at Jurby, Isle of Man, before being assigned to the Institute of Aviation Medicine at Farnborough, where he studied anti-aircraft missile-guidance systems, servo-controls for high-speed aircraft and the effects of anoxia at high altitude. A few weeks before Woodhouse was demobbed, his younger brother Hugh, a screenwriter for television, was offered the chance to write Supercar, a new weekly puppet series being produced by Gerry Anderson and Arthur Provis for ATV.

Hugh asked Martin for his help and the two wrote 22 of the first season's 26 episodes. The series was sold to 100 markets in America and 40 countries and, said Woodhouse, earned Lew Grade his first million dollars; the Woodhouses split a flat fee of £80 per episode and, as the series found success, were offered an increase to £120, still with no residuals.

Anderson had come up with the outline for Supercar (a machine at home on land, in the air or underwater) and its creator Professor Popkiss and pilot Mike Mercury, but to this cast the Woodhouses added Popkiss's elderly, absent-minded assistant, Doctor Beaker, who brought a much-needed dose of humour to the action. The brothers retained the copyright on the character and, as recently as 2005-06, hoped to relaunch the doctor in his own series, Beaker's Bureau.

In 1962 Woodhouse became one of the team of writers on The Avengers; his first script introduced Honor Blackman as Cathy Gale, partner to Patrick Macnee's John Steed, and established her as an equal rather than just a sidekick. Woodhouse went on to write a number of episodes, often with scientific backgrounds that underpinned surreal, humorous and threatening situations. He wrote six episodes for Blackman and one for her replacement, Diana Rigg, which memorably saw Emma Peel in Robin Hood fancy dress (based, said Woodhouse, on a dream). Woodhouse also wrote Emerald Soup (1963) – a children's science-fiction serial with ecological themes – and episodes of The Hidden Truth, The Protectors, The Man in Room 17 and Dr Finlay's Casebook, before deciding to try his hand at writing a novel.

The result was Tree Frog (1966), which introduced Giles Yeoman, a research scientist on loan to the scientific section of the Department of Special Intelligence. The Tree Frog project is a lightweight, pilotless drone undetectable by radar; Yeoman suspects that the project is not all it seems and finds himself a marked man in the middle of a double-bluff. Marghanita Laski named it her favourite thriller of the year and, in 1967, Woodhouse moved to Los Angeles, hoping to turn it into a film.

He subsequently lived in the West Indies (Barbados, Grenada, Montserrat), writing a number of Giles Yeoman sequels (Bush Baby, Mama Doll, Blue Bone, Moon Hill), each one centred on espionage and technology – early precursors to today's technothrillers. Phil and Me (1970) was a comedy-suspense novel set in the Caribbean; a later non-series novel, The Remington Set (1975), a cops'n'robbers thriller, appeared under the name John Charlton. In Montserrat, Woodhouse met Robert Ross, an expert on Leonardo da Vinci. Little is known about Leonardo's movements when he was in his 20s, which allowed the two to co-write The Medici Guns (1974), in which Leonardo is employed by Lorenzo the Magnificent to bring about an end to a siege at Castel del Monte; it was followed by two sequels, The Medici Emerald (1976) and The Medici Hawks (1978). His last novel, Traders (1980), concerned Afghanistan and the arms trade.

Woodhouse married Penny Lynn Stallings (they later divorced), with whom he had a son, Matthew, and a daughter, Camille, and the family moved back to Britain in 1974. In the 1980s he worked as a freelance programmer and system designer, developing programmes for e-commerce companies and stock market trading simulators. He also co-wrote the non-fiction Successful Team Building (1992).

Tall and amiable, Woodhouse was a keen skier (breaking bones more than once) and mountaineer; among many notions he worked on over the years was an idea to open a restaurant in a cave. Woodhouse is survived by his children.

• Martin Charlton Woodhouse, writer, born 29 August 1932; died 15 May 2011

After writing a number of tongue-in-cheek thrillers shot through with action, cynicism and humour, Woodhouse combined many of his interests (electronics, computers, writing) in creating the first e-books. His programme, Illumination, developed in 1987-88, was capable of "publishing" full-length novels, with both text and graphics, on a 3.5in floppy disc. Between 1992 and 1995, Illumination Publishing produced some 20 e-books, from volumes of poetry and children's short stories, to illustrated brochures and a 190-page colour graphic novel. In recent years he had been developing the Lightbook, an e-reader powered by sunlight that could be mass produced for as little as $10 per unit and used for education in developing nations.

Woodhouse was born in Romford, Essex, the son of a local doctor, Robert Woodhouse, and his wife, Josephine, who wrote verse as Anthony Woodhouse and won the Newdigate prize for English verse while she was at Oxford. Martin was educated at the cathedral choir school, Salisbury, and Oundle school, Northamptonshire, well away from the blitz in London. His older half-brother, Robert, a Mosquito pilot with the RAF's 107 Squadron, was killed over Arnhem in 1944.

Woodhouse studied for a BA in natural sciences at Downing College, Cambridge, before attending medical school at St Mary's hospital, Paddington. He studied experimental psychology under Richard Gregory and did postgraduate research at the Medical Research Council Applied Psychology Unit, where he designed and built the Logical Truth Computer (LTC, nicknamed Lettuce) to investigate and compare the differences between human and machine intelligence.

His research was interrupted when he was called up for national service with the RAF in 1958, serving as a pilot officer at Jurby, Isle of Man, before being assigned to the Institute of Aviation Medicine at Farnborough, where he studied anti-aircraft missile-guidance systems, servo-controls for high-speed aircraft and the effects of anoxia at high altitude. A few weeks before Woodhouse was demobbed, his younger brother Hugh, a screenwriter for television, was offered the chance to write Supercar, a new weekly puppet series being produced by Gerry Anderson and Arthur Provis for ATV.

Hugh asked Martin for his help and the two wrote 22 of the first season's 26 episodes. The series was sold to 100 markets in America and 40 countries and, said Woodhouse, earned Lew Grade his first million dollars; the Woodhouses split a flat fee of £80 per episode and, as the series found success, were offered an increase to £120, still with no residuals.

Anderson had come up with the outline for Supercar (a machine at home on land, in the air or underwater) and its creator Professor Popkiss and pilot Mike Mercury, but to this cast the Woodhouses added Popkiss's elderly, absent-minded assistant, Doctor Beaker, who brought a much-needed dose of humour to the action. The brothers retained the copyright on the character and, as recently as 2005-06, hoped to relaunch the doctor in his own series, Beaker's Bureau.

In 1962 Woodhouse became one of the team of writers on The Avengers; his first script introduced Honor Blackman as Cathy Gale, partner to Patrick Macnee's John Steed, and established her as an equal rather than just a sidekick. Woodhouse went on to write a number of episodes, often with scientific backgrounds that underpinned surreal, humorous and threatening situations. He wrote six episodes for Blackman and one for her replacement, Diana Rigg, which memorably saw Emma Peel in Robin Hood fancy dress (based, said Woodhouse, on a dream). Woodhouse also wrote Emerald Soup (1963) – a children's science-fiction serial with ecological themes – and episodes of The Hidden Truth, The Protectors, The Man in Room 17 and Dr Finlay's Casebook, before deciding to try his hand at writing a novel.

The result was Tree Frog (1966), which introduced Giles Yeoman, a research scientist on loan to the scientific section of the Department of Special Intelligence. The Tree Frog project is a lightweight, pilotless drone undetectable by radar; Yeoman suspects that the project is not all it seems and finds himself a marked man in the middle of a double-bluff. Marghanita Laski named it her favourite thriller of the year and, in 1967, Woodhouse moved to Los Angeles, hoping to turn it into a film.

He subsequently lived in the West Indies (Barbados, Grenada, Montserrat), writing a number of Giles Yeoman sequels (Bush Baby, Mama Doll, Blue Bone, Moon Hill), each one centred on espionage and technology – early precursors to today's technothrillers. Phil and Me (1970) was a comedy-suspense novel set in the Caribbean; a later non-series novel, The Remington Set (1975), a cops'n'robbers thriller, appeared under the name John Charlton. In Montserrat, Woodhouse met Robert Ross, an expert on Leonardo da Vinci. Little is known about Leonardo's movements when he was in his 20s, which allowed the two to co-write The Medici Guns (1974), in which Leonardo is employed by Lorenzo the Magnificent to bring about an end to a siege at Castel del Monte; it was followed by two sequels, The Medici Emerald (1976) and The Medici Hawks (1978). His last novel, Traders (1980), concerned Afghanistan and the arms trade.

Woodhouse married Penny Lynn Stallings (they later divorced), with whom he had a son, Matthew, and a daughter, Camille, and the family moved back to Britain in 1974. In the 1980s he worked as a freelance programmer and system designer, developing programmes for e-commerce companies and stock market trading simulators. He also co-wrote the non-fiction Successful Team Building (1992).

Tall and amiable, Woodhouse was a keen skier (breaking bones more than once) and mountaineer; among many notions he worked on over the years was an idea to open a restaurant in a cave. Woodhouse is survived by his children.

• Martin Charlton Woodhouse, writer, born 29 August 1932; died 15 May 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment