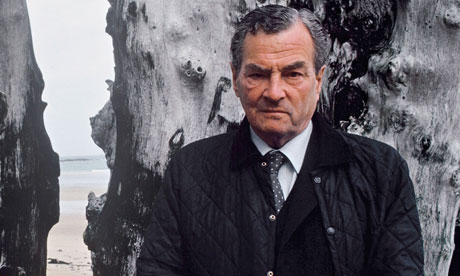

Last of the line: Patrick Leigh Fermor pictured in 1992.

Envy, they say, is the writer's fault, but no writer of my acquaintance resented the pre-eminence of Patrick Leigh Fermor, the supreme English travel writer, who died on Friday after 96 years of a gloriously enviable life. He stood alone.

One must not gush, but like Venice, Château d'Yquem or a Rolls-Royce of the 1930s, he really was beyond competition; and since so far as I know everybody liked him, everyone enjoyed his mastery.

Few of us want to be called travel writers nowadays, the genre having been cheapened and weakened in these times of universal travel and almost universal literary ambition, but Leigh Fermor made of the genre a lovely instrument of grace, humour and reflection. He was, in my view, perhaps the last of a line that began with Alexander Kinglake and Eothen in the 1840s and depended for its style upon the easygoing confidence of the best of Englishness, in the best days of England. Nobody could be less racist, insular or pompous: but then the best of England never was.

For in many ways Paddy Leigh Fermor really was the ideal Englishman – good-looking in a gentle sort of way, strong but not beefy, full of fun, poetical and scholarly, metaphysically inclined, with a wife, a house, a cat and a calling, all of which he loved. Besides, he was a war hero.

In an aesthetic sense he was lucky to live when he did, because it enabled him to fight a fine war in a just cause. He was no Rupert Brooke or Wilfred Owen, because to fulfil the heroic image completely he ought to have died in battle, preferably at Gallipoli, but nevertheless he was a hero in a particularly English (as against British) kind – an individualist hero, quirkily bold, adventuring on his own or with friends and enjoying himself.

In war as in peace, he was one of a kind. He went to no university, but he was one of God's own autodidacts, with a prodigious gift for languages and a fascination with the most intricate, subtle and sometimes obstruse constructions of historical learning. Partly because he chose to live for much of his life in the southern Peloponnese, he was especially good at relating modern to ancient worlds, so that travelling with him, if only on the page, was like simultaneously travelling through several ages.

Nothing illustrates his life better than the story of his most famous book, an uncompleted trilogy about his adolescent pedestrian journey across Europe, from Hook of Holland to Constantinople, just before the second world war. There is nothing ordinary about this work. In it a solitary young man, scarcely out of school, pits himself in a literary sense against the astonishingly varied social and political circumstances of 1930s Europe. He earns his living by his wits, by his outgoing personality, by his willingness to have a go at anything, and by drawing pictures of people, and he makes friends with Europeans of every class and kind, from the wildest of aristocrats to the grizzliest of peasants – treating them all, as Kipling would have liked, just the same. The journey lasted several months. The trilogy took a lifetime to write. Leigh Fermor was 19 when he started his walk, but did not put pen to paper (A Time of Gifts, 1977) until he was in his sixties. The second volume (Between the Woods and the Water) appeared 10 years later, while the third volume has never been published, and perhaps remains unfinished – eagerly expected for 30 years already, and now presumably awaiting its dramatic posthumous revelation.

Nothing could be more Leigh Fermorian! Part of the original manuscript was lost and Leigh Fermor had to rewrite it long after the event, which perhaps gives the work an extra element of the imagination. He was hardly more than a boy when he started thinking about it, a nonagenarian when he last laid down his pen, and in between he had not only fought his war and become famous, but had produced several other books of travel, memoir and fiction.

But just as, so it seems to me, the central character of the narrative remains essentially unaltered, certainly unabashed, from start to quasi-finish of his odyssey, so the character of Leigh Fermor himself remained instantly familiar, in frail old age as in irrepressible youth.

He was a true travel writer. Most of his books were based upon movement and actual journeys remained the basis of his studies of place. Unlike most of his successors and disciples, he was not world-ranging. He wrote little about Africa or India or China, let alone Australasia or the United States. Europe, and especially Grecian and Byzantine Europe, was essentially his stomping-ground and the classic travel works of his maturity were about two regions of Greece, Mani and Roumeli.

The first of his published books, Travellers' Tree (1950), was indeed a journey through the Caribbean Islands, and won him immediate recognition, but for me its best moment occurs when Leigh Fermor, wandering around the parish churches of Barbados, comes across the graveyard inscription: Here lyeth ye body of Ferdinando Palaeologus, descended from ye Imperial lyne of ye last Christian Emperor of Greece. Died 3 Oct 1679. Forty years after the book's publication I wrote to reassure Paddy that the inscription was still in good order. "How very nice to know," he replied, "that you and our old pal Palaeologus are prospering!"

He wrote that message on a picture postcard of Kardamyli, where he and his wife were living in the adorable house above the sea that they had themselves designed, and he wrote it in a form that had become by then a sort of Leigh Fermor trademark. The text was written within a loosely scrawled cloud, and around the cloud, meticulously disposed, were 10 or 12 birds, seabirds I suppose, which gave the ensemble a delightful sense of liberty. Leigh Fermor was an able artist, as those clients of Mitteleuropa had discovered, and he used this agreeable device to make the mere signing of a book, or the dashing off of a picture postcard, a small ceremony of goodwill.

I know little about Leigh Fermor's religious convictions, although he did frequently retreat into monasteries, and once wrote a book (A Time to Keep Silence, 1957) about his experiences. He ended the writing of it at the top-storey window of a Benedictine priory in Hampshire and said of the blessing he found there that it brought "a message of tranquillity to quieten the mind and compose the spirit". He was certainly a man of profound contemplative habit, a kind man, and in the course of my own long if sporadic correspondence with him I was chiefly impressed by his generous association with nature – the world, so to speak, seen from that top-storey window.

Here, he once writes, "a big blackbird has settled on my window sill. Can't move!" Here he is sorry to report that Tiny Tim the cat is "in a better world, mousing above the clouds". And time again Paddy reports that from the table where he writes under his pergola he can see the dolphins of the Mediterranean delightfully swimming up the bay.

A complex soul, then, but with a stillness at the heart of him. The obituarists, I do not doubt, will make much of his wartime guerrilla exploits – above all his part in the kidnapping of the German general Heinrich Kreipe in Crete in 1944, and his whisking away to captivity in Egypt. It was certainly a wonderfully dashing adventure, bravado at its most filmic, and it certainly illustrated one part of Leigh Fermor's multi-faceted character.

For me the most telling part of the oft-told tale, though, is an episode when he overhears the captive general, waiting in the dawn to be shipped away from the island, murmuring some lines from Horace which Paddy himself had long before translated from the Latin. He recognised them at once, and responded in kind, with five more stanzas. As he remembered half a century later, "the general's blue eyes had swivelled way from the mountaintop to mine – and when I had finished, after a long silence, he said 'Ach so, Herr Major!'"

It was very strange, the young major thought, "as though for a moment the war had ceased to exist". But I think of that moment as the silent stillness at the heart of his own often tumultuous and complex mind. Beloved as he was, rich in friendships, celebrated, successful, happy, convivial, nevertheless he struck me always as one of God's intimate loners.

One must not gush, one must not gush, but I am proud to have known him, and happy in my sadness to be writing about him now.

LIFE AND TIMES

■ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, born in London in 1915, was the architect of one of the most daring feats of the second world war, the kidnapping of the commander of the German garrison on Crete in April 1944 while working for British special operations on Crete.Dressed as a German police corporal, he and a fellow British soldier ambushed and took control of a car containing General Heinrich Kreipe, the island's commander, and bluffed their way through 22 checkpoints.

After three weeks avoiding German searches, Kreipe was taken off the island by boat. The daring escapade was later turned into a film, Ill Met by Moonlight, in which Leigh Fermor was played by Dirk Bogarde.

■ He wrote some of the finest pieces of travel writing and has been described as a "cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene". His most celebrated book, A Time of Gifts (1977), told of a year-long walk from Rotterdam to Istanbul in 1934, when he was 18.

■ He married Joan Elizabeth Rayner, daughter of the first Viscount Monsell, in 1968. She died in June 2003 aged 91. There were no children.

No comments:

Post a Comment