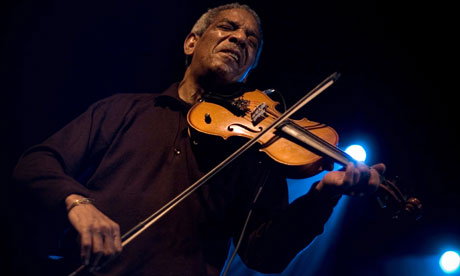

Billy Bang, a Vietnam war veteran, used music to express his harrowing experiences of prejudice, violence and isolation.

As the instrument often taken to represent the soul of western classical music, the violin has seemed untouchable to many jazz artists. However, a few have sidestepped its symbolic status to put this dazzling sound-source to their own improvisatory uses. The swing musicians Joe Venuti, Stuff Smith and Stéphane Grappelli were jazz-violin pioneers in the 1930s and 40s; Jean-Luc Ponty and Didier Lockwood introduced a rock-influenced fusion in the 1970s; and others took the violin into the sometimes abrasively uncompromising world of free improvisation: Billy Bang, who has died of lung cancer aged 63, was one of the most respected, skilful and influential. Bang's playing sometimes erupted with a jackhammering, snaredrum-like percussiveness, his solos jostling with undertones, unexpectedly baroque flourishes and implied harmonies that darted like shoals of fish around and under the dominant melodic line. But as well as a "sheets of sound" approach that could suggest the saxophone soliloquies of John Coltrane, Bang could also exhibit a wheedling, mischievous quality, reminiscent of the soprano sax lines of Steve Lacy. Bang was a genuine original, whose radicalism of method was always balanced by a powerful lyrical sense, a driving inner beat and the earthiness of the blues. He was born William Vincent Walker in Mobile, Alabama, and in early childhood moved to Harlem, New York, with his mother. He learned the violin at the prep school he attended on a scholarship. There, he gained his nickname (from a cartoon character), played with the folk singer Arlo Guthrie and taught himself drums and flute. Frontline military service in Vietnam had a seismic effect on Bang; being small in stature, his job was to confront North Vietnamese soldiers in boobytrapped tunnels with just a flashlight and a .45 pistol. Drugs, alcohol and mental distress dogged Bang on his return to the US. While living in the Bronx, New York, he became involved with a revolutionary political group. On a trip to a pawnshop to buy guns, he ended up choosing a $25 violin instead. An older violinist, Leroy Jenkins (an early free-jazz exponent who became his teacher), inspired him to believe that through music he could express his harrowing experiences of racism, violence and isolation. With Jenkins's encouragement, Bang became a key figure in New York's informal "loft jazz" scene of the 1970s – though at the outset he knew comparatively little of the jazz tradition and was yet to embrace the work of Coltrane or Ornette Coleman, the saxophonists who were to become powerful influences. In a 2005 interview with Jazz Times, Bang recalled his epiphany as being a simple realisation: "I'm determined to become a musician now. Not a violinist, but a jazz musician who happens to play that instrument." In 1977, following sessions at the experimental La MaMa theatre, Bang co-founded the String Trio of New York, with the guitarist James Emery and the bassist John Lindberg. This was to become a seminal group operating on the borders of classical chamber music and free improvisation. It passed through several incarnations after Bang left in 1986, with the jazz-violin star Regina Carter becoming one of its most celebrated later members. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Bang performed in America and Europe, often with senior figures from the first wave of free jazz (including the trumpeter Don Cherry, the saxophonists Frank Lowe and Sam Rivers, and the drummer Dennis Charles). He also played in the avant-funk drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson's group Decoding Society in the late 70s, and alongside the fierce, Hendrix-like guitarist Sonny Sharrock in Bill Laswell's fearsome punk-jazz ensemble Material in 1981. Bang formed several genre-crossing jazz and improv co-operatives, such as the free-bop group the Jazz Doctors (with Lowe) and the rap-influenced Forbidden Planet. He was popular in Europe, having regularly toured the continent from 1977 onwards. The Italian label Soul Note released much of his best work, including the mercurial Rainbow Gladiator in 1981 (with the saxophonist Charles Tyler and the pianist Michele Rosewoman) and Tribute to Stuff Smith (1992), which featured the free-jazz bandleader Sun Ra, another experimenter with deep traditional roots, in a rare sideman's role. Bang had performed with the Sun Ra Arkestra in the 1980s. He relocated to Berlin in 1996, and also shifted to the Canadian label Justin Time – a move that brought the violinist closer to a lyrical standard-song style than at any time in his career. At Justin Time, the producer Jean-Pierre Leduc encouraged Bang to make the Asian-influenced album Vietnam: The Aftermath (2001), for which he enlisted a gifted band including Lowe and the trumpeter Ted Daniel, another Vietnam veteran. Leduc recently observed that the players were often overcome by emotion during that session, although the leader was at pains to balance music that was reflective of Vietnamese life with representations of the traumas of combat. The tracks Tunnel Rat and Tet Offensive reflected the latter. The follow-up album, Vietnam: Reflections (2005), included the composer and saxist Henry Threadgill, four American Vietnam war veterans and two Vietnamese musicians. The violinist went back to Vietnam for a documentary film, Redemption Song (2008), which introduced him to a new audience. Bang continued to tour Europe and the US regularly, sometimes working with the Art Ensemble of Chicago's bassist Malachi Favors Maghostut, the saxophonist David Murray, the fusion ensemble Sonicphonics, and his long-term collaborator Lowe, until the latter's death in 2003. Their last concert together was issued – as Lowe's dying wish – on the CD Above and Beyond: An Evening in Grand Rapids (2007). Bang is survived by his partner, Maria; his daughters, Hoshi and Chanyez; his sons, Jay and Ghazal; and a granddaughter. • Billy Bang (William Vincent Walker), musician, born 20 September 1947; died 11 April 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment