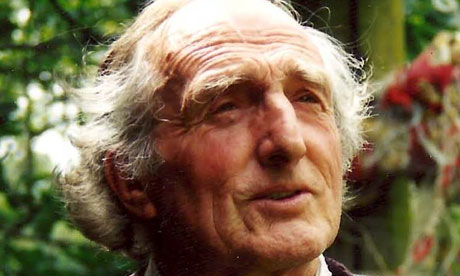

Donald Hewlett, right, as Colonel Reynolds with Windsor Davies in It Ain't Half Hot Mum.

Donald Hewlett, who has died of pneumonia aged 90, was already in his mid-50s and had a long career as a screen character actor behind him when he was cast as Colonel Reynolds, commanding officer of a second world war Royal Artillery concert party, in It Ain't Half Hot Mum (1974-81). In public, he found people recognising not just his face, but also his voice.While Battery Sergeant Major Williams (Windsor Davies) tried to instil discipline into Bombardier "Gloria" Beaumont (Melvyn Hayes), the singer Gunner "Lofty" Sugden (Don Estelle), the pianist "Lah-de-Dah" Gunner Graham and others, Colonel Reynolds enjoyed the easy life, lounging around, sipping gin and conducting an affair with Daphne Waddilove-Evans (Frances Bennett), whose husband was away in the Punjab.

While Battery Sergeant Major Williams (Windsor Davies) tried to instil discipline into Bombardier "Gloria" Beaumont (Melvyn Hayes), the singer Gunner "Lofty" Sugden (Don Estelle), the pianist "Lah-de-Dah" Gunner Graham and others, Colonel Reynolds enjoyed the easy life, lounging around, sipping gin and conducting an affair with Daphne Waddilove-Evans (Frances Bennett), whose husband was away in the Punjab.

The sitcom was written by the Dad's Army creators David Croft and Jimmy Perry. Perry himself had taken charge of a concert party while serving with the Royal Artillery during the war. Croft and Perry later gave Hewlett the role of Lord Meldrum in the "upstairs, downstairs" sitcom You Rang, M'Lord? (pilot 1988, series 1990-93). As head of an aristocratic, 1920s family, George Meldrum ran the Union Jack Rubber Company and was a respected member of the gentry – a position threatened by his extra-curricular activities with Lady Agatha Shawcross (Angela Scoular). It was often left to the butler, Alf Stokes (Paul Shane), to create diversions and cover up the relationship. Despite his wealth, the peer paid his staff badly.

Hewlett, who came from a wealthy family himself, was born in Northenden, Cheshire. His father, Thomas, owned the Anchor Chemical Company, based in the Manchester suburb of Clayton. Hewlett was 10 when his mother died. While attending Clifton college in Bristol, he started producing revues. Then, at Cambridge University, where he studied meteorology and geography, he was a member of the Footlights revue.

However, his course was curtailed by the outbreak of war, during which he served in the Navy as a meteorologist in Orkney – providing reports for Lord Mountbatten – and set up Kirkwall Arts Club in a temperance hall. He was later responsible for looking after Japanese prisoners-of-war in Singapore, where he organised entertainment for British troops.

After the war, Hewlett trained at Rada, winning the Athene Seyler award for comedy. He left it to his younger brother, Clyde – who was later made a life peer for his services to the Conservative party – to take over the family business. Hewlett started his professional career with the repertory company at Oxford Playhouse, where he soon became a leading man, acting alongside Christine Pollon, whom he married in 1947. He also helped to boost the career of Ronnie Barker, who was working for the theatre's publicity department. He got chatting to Barker after seeing him sticking up posters, and recommended him for a speaking role in the next production. In 1951, Hewlett and Barker – in costume – provided a local spectacle as they shared a pony-and-trap trip around Oxfordshire to promote a production of Charley's Aunt.

Hewlett also toured with the husband-and-wife team of Cicely Courtneidge and Jack Hulbert, and appeared in the West End musical Grab Me a Gondola (Lyric theatre, 1956-57) and the revue … And Another Thing (Fortune theatre, 1960).

He made his film debut, alongside Sid James, Tony Hancock and Peter Sellers, in the comedy Orders Are Orders (1954). Although Hewlett subsequently appeared in the school comedy Bottoms Up (starring Jimmy Edwards, 1960), most of his screen career was spent on television. He played Captain "Snooty" Pilkington, son of the retired army officer of the title, in the sitcom The Adventures of Brigadier Wellington-Bull (1959). He then appeared mostly in dramas, including episodes of The Saint (1965), The Avengers (1966) and Callan (1967), as well as the Dennis Potter plays Vote, Vote, Vote, for Nigel Barton (1965) and Message for Posterity (1967).

In a 1965 episode of Coronation Street, he was Bob Maxwell, a married solicitor who offered Elsie Tanner a lift, had a heart attack at the wheel and died. He also played Sir George Hardiman in the 1971 Doctor Who story The Claws of Axos. More comedies then came Hewlett's way, including the regular role of Colonel Sutcliffe in Now Look Here (starring Ronnie Corbett, 1971-73) and Carstairs in the shortlived Come Back Mrs Noah (pilot 1977, series 1978), written by David Croft and Jeremy Lloyd.

Hewlett's last screen appearance was in a 1995 episode of the sitcom The Upper Hand. The following year, he took to the stage for the last time, alongside Ronnie Corbett, in the pantomime Mother Goose (Churchill theatre, Bromley). Epilepsy, caused by a damaged heart valve, led him to retire and he later developed Alzheimer's disease.

Hewlett's first marriage ended in divorce, as did his subsequent, 1956 marriage, to Diana Greenwood, a dressage rider. He is survived by his third wife, the actor Therese McMurray, whom he married in 1979, and their children, Patrick and Siobhan; and by two sons, Jonathan and Mark, and a daughter, Sophie, from his second marriage.

• Donald Marland Hewlett, actor, born 30 August 1920; died 4 June 20