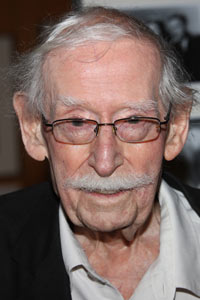

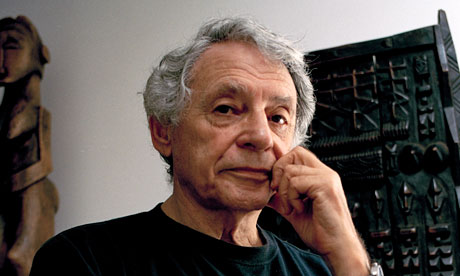

Arthur Goldreich in 2005. ‘He could charm the birds out of the trees’. Photograph: Sean Smith for the Guardian

In the midst of one of the tensest periods of the anti-apartheid struggle, a single-winged Cessna aircraft carrying two priests in dog collars took off from an airstrip in Swaziland and flew across South African territory to British Bechuanaland. The "clerics" stepped out to a rapturous welcome from the local African National Congress. The escape of the freedom fighter Arthur Goldreich while on remand in a Johannesburg prison had been accomplished.

Goldreich, who has died aged 81, was part of the underground leadership of the ANC's liberation army, Spear of the Nation, that was captured in a police raid on Liliesleaf farm, Rivonia, in July 1963. Goldreich was the tenant of the property and had been living a seemingly harmless existence with his teacher wife, Hazel, and two sons, Nicholas and Paul – horse riding in the countryside and holding a job as a designer for a Johannesburg department store. (He designed the sets for King Kong, the black musical that played in London in the early 1960s.) So integrated were the Goldreich family in the secret life of the farm that on one occasion, as the high command met to discuss tactics, five-year-old Paul was found crawling around under the table.

Living at the farm, too, in the early 1960s was "David", purportedly a domestic servant but otherwise known as Nelson Mandela, the guerrilla commander-in-chief. Mandela discussed tactics with Goldreich, explaining in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom (1994), that "Arthur had fought with the Palmach, the military wing of the Jewish National Movement in Palestine. He was knowledgable about guerrilla warfare and helped fill in many gaps in my understanding."

Mandela was already in prison by the time the raid on the farm took place, but was brought back to court and put on trial alongside others arrested that day. The following year, at the conclusion of what became known as the Rivonia trial, he and seven other defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Goldreich was born in Johannesburg, the son of a furniture dealer. The family moved to Pietersburg (now Polokwane) in the northern Transvaal. At his Afrikaans school, his German language teacher gave out Hitler Youth magazines for the class to read. Arthur wrote to the pro-British prime minister, Jan Smuts, demanding to be taught Hebrew. The wish was granted.

On leaving school, he enrolled as an architectural student in Johannesburg, but as a dedicated Zionist he gave up his studies in 1948 to fight in Israel's war of independence. The war coincided with the Afrikaner nationalist victory in the South African general election. Goldreich later said that he was driven by "the Holocaust and the struggle against British colonialism, but the Nats winning the election left me in no doubt about what I had to do".

He left Israel to study industrial design in London before returning home. He had married Hazel Berman, who was active in the Young Communist League. Goldreich, though still preoccupied with Zionism, was moving to the left, and joined the underground Communist party. As the ANC prepared to launch its armed struggle, the Goldreichs were persuaded to rent Liliesleaf as the headquarters of its high command. Goldreich was the ideal cover. "A flamboyant person," Mandela said of him, "he gave the farm a buoyant atmosphere."

After the police raid, the Goldreichs were held under the 90-day law at Marshall Square, Johannesburg's main police station, but discipline there was surprisingly lax. One day Johan Greeff, a teenaged policeman with no idea of the importance of his charges, was switched to overseeing the "political" cells. The detainees found him obliging. He would collect food and cigarettes, and on one occasion a pair of shoes and a new suit. Goldreich even persuaded the station commander to allow him out of the building, accompanied by Greeff, to visit his barber. "Arthur could charm the birds out of the trees," Hazel says, "and Greeff was easy meat."

Greeff was interested in fast cars, and had his eye on a Studebaker Lark. He agreed to facilitate their escape for 4,000 rand (then £2,000) in cash. One quiet Saturday night, he opened the inner and outer doors, then faked an injury. Goldreich and a civil rights lawyer, Harold Wolpe, made good their escape and, despite a furious nationwide manhunt, were smuggled into Swaziland, where they lay low in the home of a sympathetic Anglican priest before setting out for London.

Goldreich returned to Israel, becoming a professor at the Bezalel academy of arts and design, part of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He later spoke out firmly against the brutality and inhumanity imposed on the people of occupied Palestine. Hazel was released after three months, having refused to join the escapees because of concerns about her children. The couple later divorced and Goldreich remarried.

Greeff did not fare as well. He was arrested within the hour, before he was able to collect the bundle of notes from a go-between, Paul Joseph. He was sentenced to six years in prison, paroled after serving two years. Thirty years later, with apartheid ended, Joseph raised the matter of his payment. The escapees, as well as the ANC, said the debt should be settled. Goldreich said Greeff was "a kind man and paid a severe price. We owe him a lot." More than 40 years after the debt was incurred, it was at last settled when a courier arrived at Greeff's motor repair shop in the remote northern Cape to deliver an amount believed to be in the region of SAR110,000 (£10,000).

Goldreich is survived by Nicholas and Paul; by his children, Amos and Eden, from his marriage to Tamar, who predeceased him; and by five grandchildren.

• Arthur Joseph Goldreich, freedom fighter and artist, born 25 December 1929; died 24 May 2011